Wrapping it up sustainably

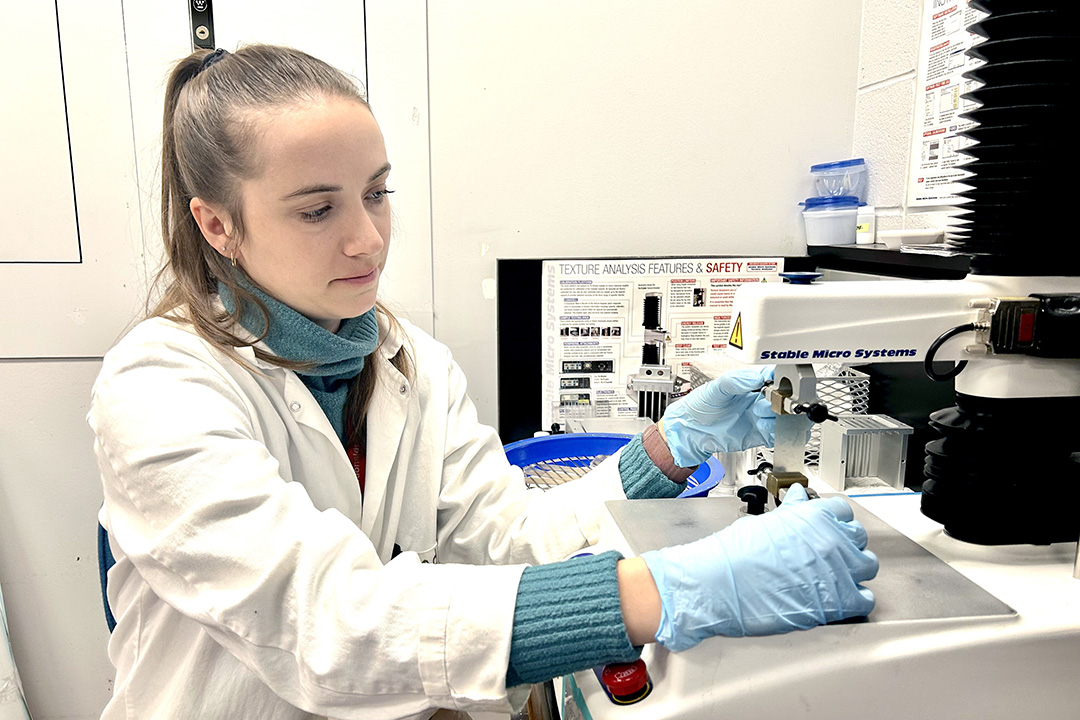

USask researchers investigate pulse proteins to replace petroleum in packaging

By Joanne PaulsonEvery time you unwrap a grocery store steak to throw on the barbecue, you are also throwing a piece of unrecyclable, undegradable plastic into the garbage bin.

From there, that bit of petroleum-based waste heads to the landfill, there to remain for a long time or to find its way into freshwater resources.

There is a better way, and Dr. Michael Nickerson (PhD) is working on it.

“There’s a huge demand on landfills. Microplastics are entering oceans. It has a huge impact,” said Nickerson, the Saskatchewan Agriculture and Food Research Chair in Protein Quality and Utilization in the Department of Food and Bioproduct Sciences in the College of Agriculture and Bioresources at the University of Saskatchewan (USask).

“There’s a huge commitment from Canada in terms of enhancing environmental sustainability. There’s a big push into biomaterials and away from petroleum-based plastics. There’s a big demand on natural resources to produce them and also dispose of them. Organic materials can degrade quickly under the right conditions.”

As the research chair, his role is to find value-added crop ingredient uses for food, feed and biomaterial applications.

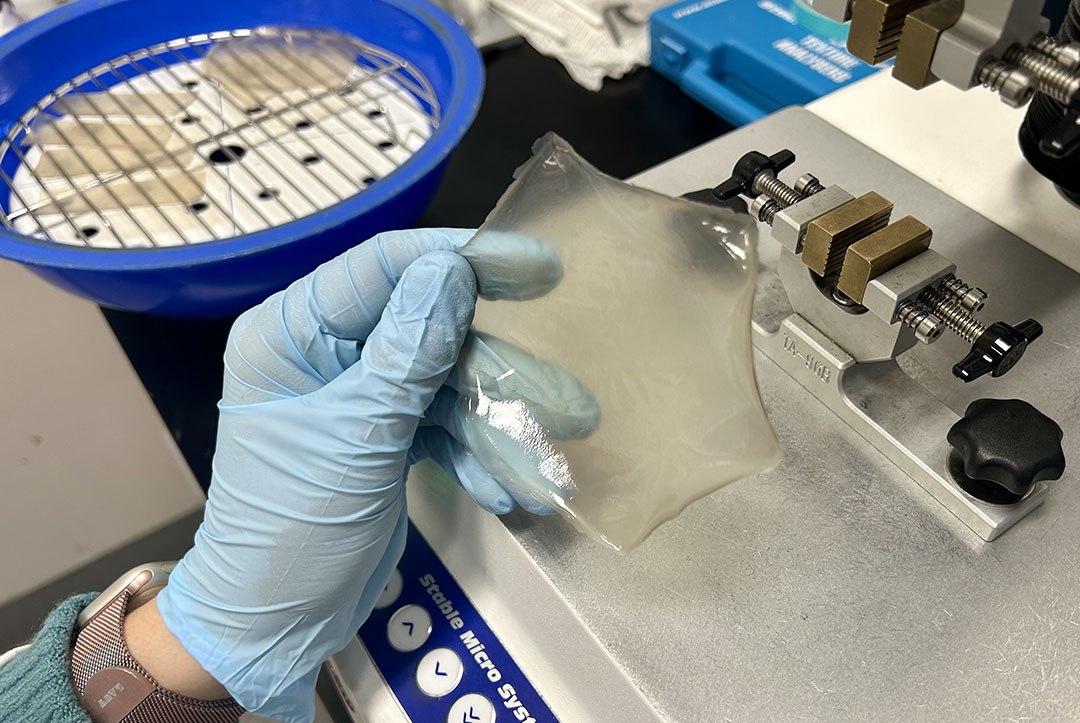

Nickerson is presently focused on food-based “films” made from pulse and other crop proteins.

“We’re trying to target a certain application for meat. We’re trying to replace the synthetic packaging that wraps around your meat—the plastic wrap—and replace it with this protein-based one that is more of an active packaging,” he said.

Nickerson and his team are also incorporating antimicrobial agents, such as essential oils, which are approved for food use.

“The idea is that we can control these active ingredients over time. We can not only protect the food but extend the shelf-life of these meat products.”

One thing leads to another

A related innovation Nickerson is working on with colleague Dr. Supratim Ghosh (PhD) is using nanoscience to include oil droplets that manage the diffusion of antimicrobial agents through the film.

By changing the microstructure of the film, “we can get different release profiles and different shelf-life. We have a couple of students working on it now and doing some meat trials to show efficacy of this type of packaging.”

Meanwhile, Nickerson and his team are also finding some “really interesting results” branching off from the main project.

One of these is a formulation of the protein film that dissolves in water, which could lead to oral delivery systems of vitamins or oil-soluble nutraceuticals, for example.

“Sometimes in science you come up with one thing and it opens up more doors,” he said. “We’re starting to see other opportunities emerging from the science from this project.”

The course of new science always presents challenges, and one in this project is managing the colour pigments natural to the crops to obtain a clear film.

The other looming challenge will be scaling up—finding the technologies and willing companies to mass produce the film.

At the end of the three-year project, it will be time to seek additional funding and attract industrial partners to the project.

“We’re at the bench-top level and we have to change the way we process this to make it high throughput, which means extrusion and other technologies. We also need to find an industry that can actually deal with that,” Nickerson said.

“But we want to show proof of concept and then approach some companies to help manufacture. How can we adjust this prototype and what are the challenges?”

Pulse market worth growing

The raw materials for Nickerson’s work are on the ground in Saskatchewan.

The province is a leading producer and exporter of pulses, predominantly lentils and peas, but this project may lead to increased planting of an up-and-coming Saskatchewan crop.

That would be faba bean, a legume which fixes nitrogen in the field (thereby reducing the need for fertilizer) and offers farmers an option for rotation.

It also has higher protein levels than pea. Yellow pea, for example, contains 23 per cent protein, while faba bean has 31 per cent.

“That’s important, because when you dry process it, you can create ingredients with higher protein levels which means more money,” Nickerson said.

Indeed, part of the reason he is choosing certain crops is to enhance the diversity of ingredients produced in Saskatchewan.

There has been recent “tremendous investment” in the dry processing industry, he added, while the provincial government has said in its growth plan that it hopes to see 50 per cent of pulses processed here by 2030.

“Our goal isn’t just to make the product,” Nickerson said. “Our goal is to increase market diversification. There’s a number of companies in Saskatchewan that are processing faba beans, and the industry in the food sector are asking for this. They want the faba bean ingredients.”

Nickerson is confident the Saskatchewan food industry will come through.

“Even though there are environmental impacts of droughts and disease, there’s always going to be crops,” he said.

“There’s a huge amount of innovation at the Crop Development Centre here at the university ... and at institutes around the world, to address changes in climate and impacts on crop quality. There is a strong commitment to resilience, adaptation, and sustainability.

“I think the crop supply will always be there.”

This project is funded by Saskatchewan’s Agriculture Development Fund.

Together, we will undertake the research the world needs. We invite you to join by supporting critical research at USask.