Wild rice research puts Indigenous communities at the forefront

Understanding wild rice diversity isn’t just about crop improvement, it’s also about respecting and empowering Indigenous communities.

By Clare StanfieldDr. Tim Sharbel (PhD) has always been on what he describes as the sharp end of biotechnology. A professor in the Department of Plant Sciences, College of Agriculture and Bioresources at the University of Saskatchewan (USask), Sharbel’s work focuses on apomixis, asexual seed formation in flowering plants, a 20-year project involving high-tech evolutionary genomics methods.

If you are picturing molecular biology and microscopes, you are not wrong. But Sharbel is also working on a wild rice project that adds a whole new dimension to this scenario—a very human one, which begins with building relationships.

“It’s very exciting for me personally,” said Sharbel. “I’ve spent the last 20 years of my life in biotech, and now I go to meetings to listen to Elders and am learning a great deal.”

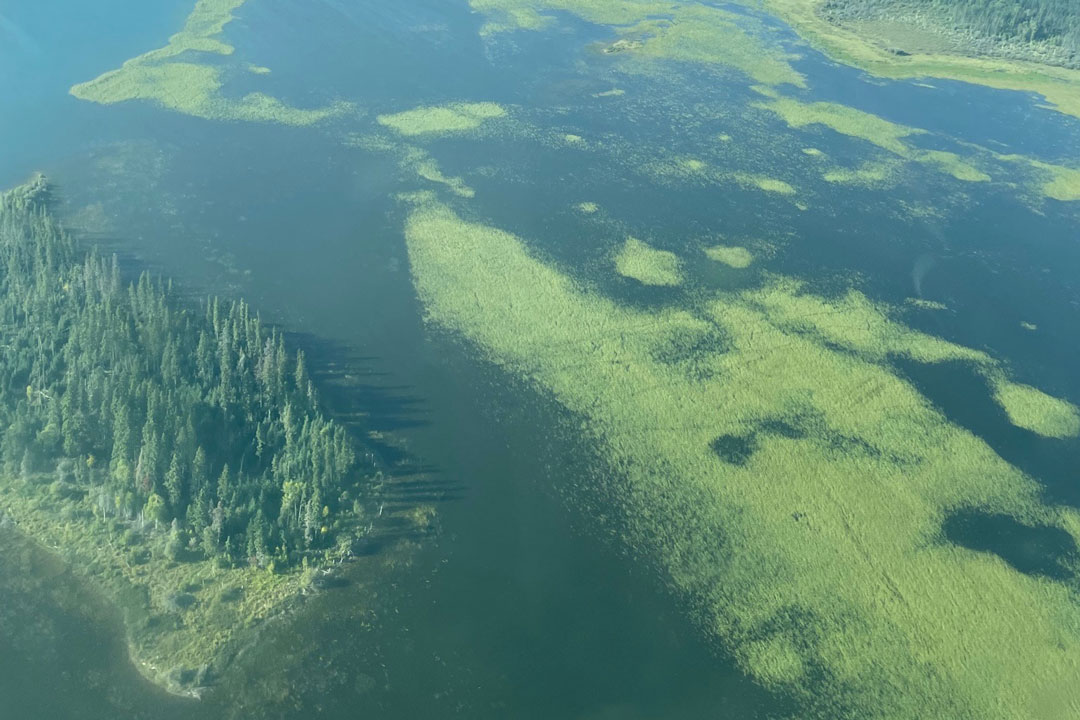

Those meetings are to discuss a new, multifaceted project to support Indigenous communities as they work to enhance the wild rice industry. About a year ago, Sharbel and his team began to work with rice samples from some of Saskatchewan’s northern lakes, but the road to get those samples to his lab was not a straight or easy one.

“It is taking a lot of time and effort and building trust to get it going,” said Sharbel.

It could not be business as usual: get funding, get rice samples, get started.

“It’s a very human, very important industry, with a plant that has been traditionally harvested for many hundreds of years.” He said, referring to First Nations wild rice production. “But it faces many problems, from planting through to selling the seeds. We are focused on what the community needs, the problems they need solved.”

Phyllis Smith couldn’t agree more. A self-employed wild rice harvester from the Métis community of Pinehouse in northern Saskatchewan, Smith says that the more she and her fellow harvesters can learn about their specific growing environments, the better.

Hearing Sharbel speak at a harvesters’ meeting in Prince Albert, Sask., Smith invited him to her community to meet the harvesters there and see how they could work together to make wild rice production in Pinehouse Lake better and stronger. That kind of cooperation and community buy-in is key.

Partnerships and permissions

Sharbel recalls a multi-institutional effort made a few years ago to put some significant funding toward wild rice research, but without Indigenous input the idea was rejected.

“In the meantime, I’d become friends with Blaine Chartrand, a professor who heads Saskatchewan Polytechnic’s BioScience Technology program and has deep Indigenous ancestry in Saskatchwan,” said Sharbel.

He and Chartrand were both interested in working with wild rice, as was Bruce Hardy, founder and CEO of Myera Group in Winnipeg. Myera is developing technologies that help bridge the gap between sustainable food supply, good nutrition and a community’s ability to manage and direct its own food economy. Hardy, who is Cree-Métis, was looking for a plant scientist to help realize his vision of determining terroirs for Canadian wild rice—just like in the wine industry where a value is placed on the unique flavour characteristics conferred by a specific geography.

“It would create that unique value proposition so they can have a brand around the community,” he said. “They can create a business model around it.”

Because terroir is community-owned, in the future, wild rice with an identified terroir could potentially be grown on a mass-scale further south in a circular fish waste, soil-based system and sold for a competitive retail price. The community would earn royalties and gain a food dividend by being able to harvest local rice for local consumption or sale into premium markets.

While this is just a small slice of what Hardy envisions for the future of food and food production in Indigenous communities, Sharbel was very excited by the ideas. “He and I first spoke about four years ago,” said Sharbel. “He was applying for money, and I started talking to people locally here.”

Slowly, relationships were built, community connections were made, and funding found from several sources, including the Saskatchewan Agriculture Development Fund (ADF), Protein Industries Canada, and Mitacs (a non-profit research funding body).

Sharbel and his colleagues began to visit northern communities to speak with Elders about working with them to gain a better understanding of the biology and natural history of wild rice production in their communities, about preserving germplasm, improving yield and quality, and protecting the future of wild rice.

As communities came on board, they have agreed to let the team collect samples of wild rice from their harvests for analyses of phenotypic and genetic variation.

Understanding the genetics of wild rice

“We have wild rice samples from about 15 or 16 lakes so far,” said Sharbel. “It’s just starting. We’ve got something like 50 lakes in total to look at. Hopefully, as we have some success, we’ll get more.”

Sharbel emphasizes that wild rice is not a monolith. Each lake has unique biological and physical characteristics, which means that wild rice populations have subtle differences based upon their history, origins, and genetics. Characterizing genetic variability of wild rice across the northern Prairies (and Canada) is the first step in understanding this traditional crop.

That starts with phenotyping and doing a statistical analysis on every sample.

“Once we do that, we can ask why they are different from each other by comparing genetic and environmental data.”

This is something that really resonated with Smith.

There are 10 wild rice harvesters in her community, each one harvests from a different lake, and they can see that grain quality, size, yield, and days to maturity differs from lake to lake, but they don’t know why. If they could find out, they could potentially use that knowledge to improve wild rice quality across all the lakes.

“There were no supports to help us work on growing more good quality wild rice, no way to get your soil and water tested,” Smith said. “And then Tim came along. I’m so glad that they want to do this. The more we know about where we’re growing our rice, the better.” So far, three harvesters from Pinehouse have sent Sharbel’s team soil, water, and rice samples from their lakes.

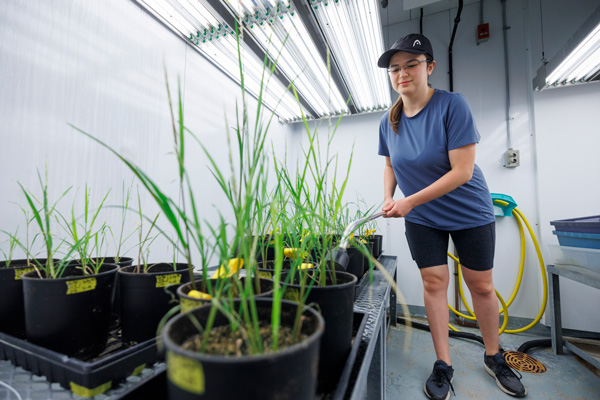

“We now have a PhD student on the team, Serena Page, looking at how we grow it,” said Sharbel. “We’re looking at the nuts and bolts of getting it to grow, and flowering is the focus now: Can we get it to flower inside a growth chamber? Can we get it to make seed?”

Sharbel explains that understanding wild rice reproduction is key.

“Seed is embryo and endosperm, and that endosperm tissue is a triploid—two genomes from mother, one from father. In the end, it’s the mother plant that determines things. Wild rice has 30 per cent more protein than white rice, more micronutrients and antioxidants. We want to see how the mother plant distributes that nutritional freight.”

Some of these answers will come from Dr. Pankaj Bhowmik (PhD), a senior research officer at the National Research Council Canada who is doing nutritional analysis in his lab, in addition to protein localization analyses at the Canadian Light Source, to determine protein content.

Ultimately, Sharbel’s team and collaborators are DNA-fingerprinting each individual wild rice sample as well as the organisms with which wild rice interacts, for example the microbiome in the mud and water in which it grows.

“The deeper we look with technology, the more we see through evolutionary analyses how everything is connected on the DNA-RNA level,” said Sharbel. “The Indigenous view of the world is that everything is connected, and now high-tech data show us the same thing—it’s beautiful.”

Together, we will undertake the research the world needs. We invite you to join by supporting critical research at USask.