Oil and water

People say oil and water don’t mix, but the exact opposite is what Supratim Ghosh in the College of Agriculture and Bioresources is working to prove with technology that holds significant potential for two disparate groups in particular—Saskatchewan farmers and beverage producers.

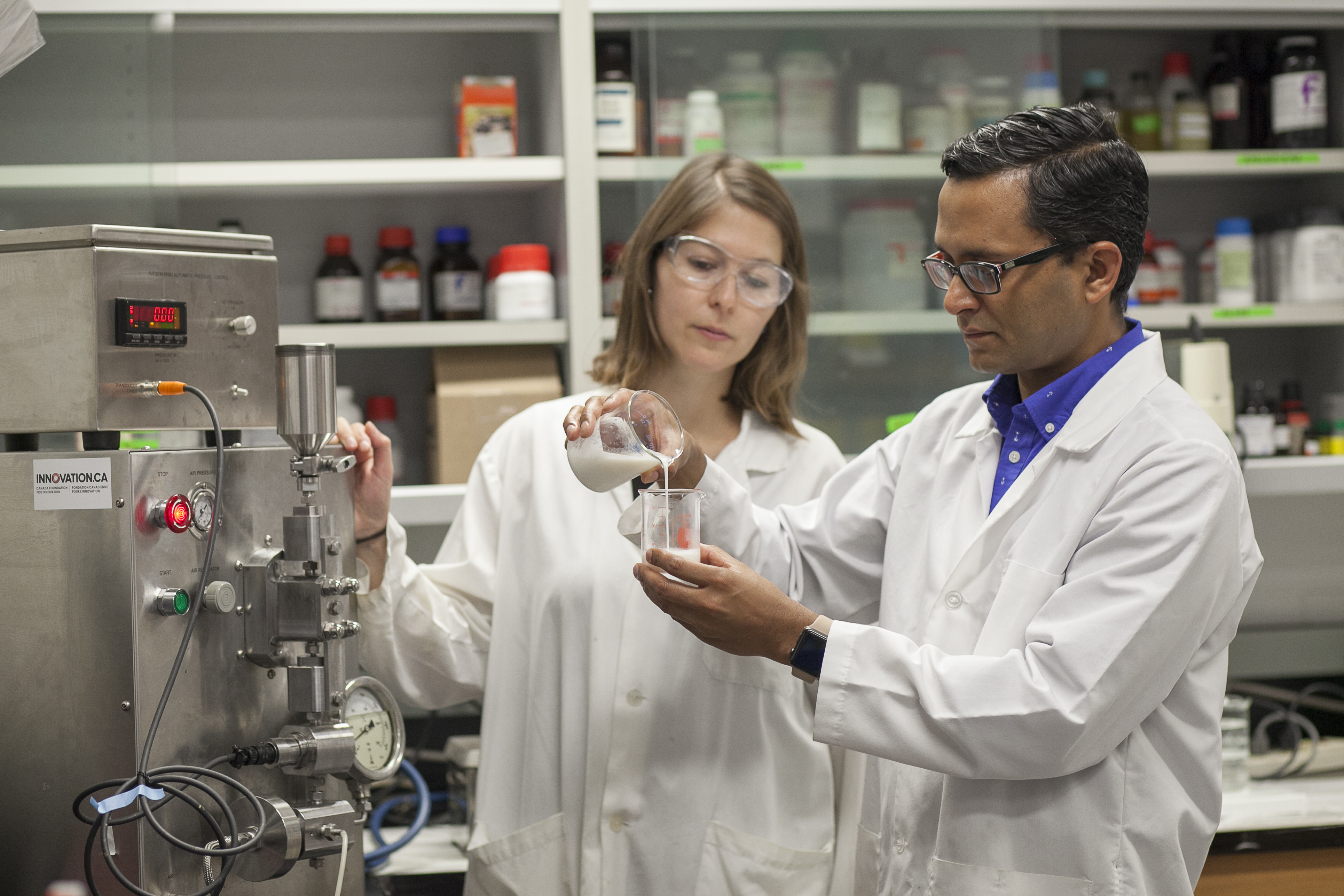

By Colleen MacPhersonGhosh, assistant professor in the Department of Food and Bioproduct Sciences, is using protein extracted from pulse crops, like peas and lentils, to coat miniscule oil droplets so they disperse evenly through liquids. It’s a complex process to create what are called nanoemulsions, but they are vital to the delivery the nutritional benefits found in ready-to-drink beverages.

“My main interest is food nanotechnology,” said Ghosh, who joined the college in 2011. “That’s a new name for the discipline where we work at a nano scale on manipulation and interaction of food structures.” To illustrate the scale, a glucose molecule is about one nanometre in size, and the period at the end of this sentence is about a million nanometres. Ghosh works on structures between 10 and 1,000 nanometres, “very small. You can’t see them.”

In ready-to-drink beverages, he explained, certain ingredients like vitamin A, an example of what is called a bioactive, do not dissolve in water but do dissolve in oil. When added to a beverage, the vitamin A is encapsulated in oil “but here’s the challenge: how do you disperse the oil in water so it doesn’t clump up? What you need are emulsifiers that coat the droplet and have a charge that forces the droplets apart,” the effect seen in magnets when similar poles repel rather than attract.

“It’s the same when you make mayonnaise,” said Ghosh. “The egg yolk acts as an emulsifier to keep the oil from separating out. We’re working on an emulsifier to keep the oil droplets dispersed evenly throughout the beverage.”

There are very few natural emulsifiers available to the beverage industry, and a growing consumer demand to move away from synthetic compounds, he explained. Gum arabic or acacia, and modified starch are two natural products “but the industry is actively seeking replacements,” and it is looking to Saskatchewan pulse crops.

“And here we come to my collaboration with Dr. (Mike) Nickerson,” said Ghosh. An associate professor in the department and the Ministry of Agriculture Strategic Research Chair in pulse protein utilization, Nickerson “has the technology to separate out the pulse protein which we then use to create nanoemulsions.”

The first step is to modify the protein structure to make it a better emulsifier. To do that, Ghosh developed a technology to loosen the natural bonds that hold the proteins together, followed by emulsifying oil with that protein solution using a high-pressure homogenizer that forces the mixture through a tiny aperture at high pressure—20,000 pounds per square inch (psi). The resulting nanoemulsions have been shown to remain stable for more than two years, he said, an important factor related to shelf life in the food and beverage industries.

One drawback is that pulse protein has a distinctive taste, he said. A preliminary study is currently underway at the Saskatchewan Food Industry Development Centre to look at whether adding the pulse nanoemulsion to existing beverages like vegetable juices and energy drinks affects the properties or taste of the products.

Ghosh also wants to make sure the pulse-protein emulsifier does not inhibit the body’s ability to absorb the beneficial ingredients. To explore that, he has set up a digestion system in his lab. “Basically we’ve used necessary chemicals, enzymes and appropriate time, temperature and mixing protocols to simulate a human stomach and intestines in beakers. We need to understand how the bioactive compounds release during digestion because unless they get into the blood stream, they won’t be of any benefit.”

Although his primary focus is on food, Ghosh said the nanoemulsion technology has potential for animal feed and other agricultural applications. In fact, he has a couple of bags of feed coated with the nanoemulsion sitting in the lab that he is evaluating for shelf life and the stability of the protein structure.

“I haven’t done any work with animal feed but this could be an opportunity to look for a collaborator and say, ‘We have the technology, would you be interested?’ Oil is already added to feed as an energy source so it is possible the droplets could be used to deliver other bioactives.”

But by far the biggest value-added application for the nanoemulsion technology is the ready-to-drink beverage market.

“Beverages are a multi-billion-dollar-a-year industry,” said Ghosh. “If crop producers got even a fraction of that using pulse protein, it would be a win-win situation.”